A correlational

evaluation of the practice of language of Mentoring

in a specific Online learning environment

Vicki Swan

2003

Back to Home

Background

Introduction and Context

Research methodology and methods

Literature Review

Community X is an educational research project with the purpose of reengaging young people that have not been in the educational system for some time, back into the learning process. Many of these young people (referred to as students) are disengaged and disillusioned with education and teachers. An online community is used as the meeting forum and each student is assigned a mentor. These mentors are qualified teachers and their role is to initially engage the student in conversation, build up their IT and literacy skills by use of the community and e-mail and then to encourage learning to take place using a variety of expert led communities and internet topic investigations. The students are invited in and kept in by the lure of secure chat rooms and e-mail. A softly, softly approach is used to gently reengage the student often gaining accreditation by stealth so that they are gaining knowledge often without realising it.

Introduction

and Context

In many cases in Community X the students involved have chosen not to

attend school, for some reason the education system has failed them. They

have no wish to be in a school environment and they certainly do not wish

to engage in learning with any teachers. This suggests that it is important

for the mentors in Community X to avoid corresponding in a teacher-like

fashion. The purpose of this research is to ascertain whether or not the

language style used by a mentor directly affects, the level of educational

reengagement of their student.

In order to assess whether mentor language style has any bearing on the educational reengagement of the student the following factors have to be determined.

1. Mentor language style.

Each week every mentor has to file a report of all the e-mails that have been exchanged with their students. A qualitative assessment has been made of a random sample of these reports to determine mentor language on a scale discussed later.

2. Educational reengagement.

Community X has a database with records of learning gains, participation and accreditation. Some of this information was used to ascertain levels of engagement by students.

Using the mentor reports and student data a correlational evaluation was made between the language style and formal accreditation statistics. The holistic understanding of mentor reports and student achievement has to be further researched to ensure that these findings have a pure relationship and are not subject to other influences.

Literature review

What is e-mail?

From the inception of network and internet tools,

the backbone of peer to peer communication was the sending of text files.

This is the essence of e-mail. Even as far back as 1978...

"...it became obvious that the ARPANET was becoming a human - communication medium with very important advantages over normal U.S. mail and over telephone calls". (Licklider 1978 cited in Bartle 2000)

No matter how complex the interface for an e-mail

client may have become with address book functions, attachment options

and mail rules, it is still fundamentally the creation of a simple text

document that can be sent to anyone else with access.

To this end, much of the available literature on virtual learning and

online communities recognises that e-mail plays an important role and

is part of a range of alternatives without assessing the implication

of the e-mail facility on communication, language and community.

Early literature maintained that e-mail was the only effective communication

tool due to the restrictions of the technology. Mason (1994) talks of

audio graphic systems requiring two phone lines being of great value

but unrealistic. Brooks (1997) talked of problems with too much web

traffic slowing down the internet and of potential storage devises that

hold more than CDroms. Within 6 years of Brooks, broadband is available

to nearly 80% of the UK population (British Telecom 2003) and DVDs are

the standard format for movies. Unfortunately, even as the internet

has developed, communication media (telephone lines, satellites etc.)

have improved and the number of community tools have increased exponentially,

e-mail has become embedded in online communication and still largely

ignored. Even recent publications emphasis the need to look at technology

rather than the communication implications. Porter (1997) talks of creating

a Virtual Classroom and Forsyth writes his book on;

"educational and administration considerations of offering a course or a selection of courses for delivery via the internet" (Forsyth 2001)

.. both without looking deeply at e-mail language

implications.

E-mail for all users

Where language has been touched upon, the assimilations tend to recognise

that we are moving into unknown territory of a new flexible language

which diverts from the traditional differences between the spoken word,

the hand written word and the typed word.

Boone elevates the written word (and by inference the e-mail word) above

the spoken word by stating:

“In the academy, in business and the other professional worlds for which we prepare our students, we place great store in documents. The text, the paper, the memorandum, he brief. Putting it in writing makes it permanent and ‘real’ in ways that speech typically does not. Documents are ‘kept’: filed in cabinets, shelved in libraries, archived in musty back rooms where, though never read or seen again, they ensure against the horror that a ‘record’ might be ‘lost.’” (Boone 2001)

Licklider however lowers the status of e-mail by stating that...

"One of the advantages of the message systems over letter mail was that, in an ARPANET message, one could write tersely and type imperfectly, even to an older person in a superior position and even to a person one did not know very well, and the recipient took no offence. The formality and perfection that most people expected in a typed letter did not become associated with network messages, probably because the network was so much faster, so much more like the telephone." (Licklider 1978, cited in Bartle 2000).

Mann and Stewart suggests that the formality of the written word is not available; stating that it is..

"used as a means to connect family, friends and colleagues, it can be relaxed private and often intimate form of one-to-one communication in which participants are mutually engaged." (Mann and Stewart 2000).

This perceived informality of e-mail is augmented

where employees have e-mail at home and they use it to share jokes and

social agendas as much as work related communications.

These papers appear to suggest that e-mail, although typed, fills more

of a role associated with the spoken word because of the tools used

and the speed that the words can be sent from one person to another.

Simpson, however, suggests that e-mail cannot fully compare to the spoken

word because...

“although e-mail appears to mimic phone conversation in some ways, even the voice cues of phone conversations are missing as well as the body cues.” (Simpson 1999)

This may go some way to explain the appearance

of the flame1 and the Troll2

. In a way that can perhaps be likened to ‘road-rage’, adults

find that they are semi anonymous, conforming to an ambiguous set of

rules that are alien to other conventions (cf letters and telephone

conversations in the e-mail scenario and walking along the footpath

for the road simile). The result is that individuals move outside normal

boundaries of decorum to the point of being abusive. The anonymity of

posting messages in an online community combined with the perceived

gravity of the written word makes the arena for defamatory comments

and misunderstandings rife.

Murphy et al discuss the presence of flame wars in communities;

“Flame war illustrates well how quickly conflict can escalate without intervention, and shows just how much time and effort are required to set matters right” (Murphy, Walker and Webb 2001)

In the Community X community there do not appear

to be many Flame Wars. This could be due to the young people not having

the preconceptions of the written word - and thus not being confused

by “ambiguous rules” (see above). It could also be that for

adults the internet is a relatively new place whereas, for children,

it is no more new than the rest of society so they easily develop a

netiqutte that they all abide by. Although outside the remit of this

paper, flame war and age, along with the road-rage comparison could

make very interesting further research.

A condense-ment of this literature review suggests that there is much

ambiguity over the nature of e-mail and its language. Falling somewhere

along a sliding scale between the formal written word and the informal

spoken word, the exact point varies from one community member to another

depending upon their age, experience, techo-literacy and the community

to which they are posting. What is recognised throughout is that this

sliding scale not only has informal advantages, but can also create

dangerous scenarios between people who are not sharing the same point

on that scale. This is where an understanding of language may improve

the effectiveness of e-mails.

E-mail and students

The purpose of this paper is to explore the use of language in e-mail,

specifically addressing levels of reengagement in students in Community X

education. Much of the research carried out to date looks at the function

of e-mail as an add-on to a classroom environment.

Simpson discussed how e-mail can be used proactively in this scenario:

“... a short text was e-mailed to several hundred new students about ten days before their first assignment was due [...] The submission rate among students was who were contacted was 3 per cent better than non-contacted students”.

Here the teacher sends an e-mail regarding a

non-virtual activity reminding the pupil of a deadline.

This ‘nudge’ by the teacher is, perhaps, less formal than

the teaching stance taken the rest of the time and fulfils a less formal

function. Porter adds to this deviation from the conventional teacher

- pupil forum when stating how;

“e-mail adds a new dimension to the way that educators and learners interact. It provides more opportunities for ‘conversation’ outside the traditional classroom and it encourages learning to take place any time, any place. Because e-mail can be sent at any time, it’s ideal way for learners and educators who don’t work typical 9-to-5 days” (Porter 1997)

This suggests that the e-mail communication between teacher and pupil

drifts into a new form simply by virtue of the platform.

This is reenforced by Brown who notes that;

“Studies in student discontinuation in distance education regularly point to the importance of students being able to access timely, relevant support” (Brown 1996 cited in Lockwood & Gooley 2001).Vygotsky suggested that;

“the best method for teaching [reading and writing] is one in which children do not learn to read and write but in which both these skills are found in play situations” (Vygotsky 1978 cited in Moll 1990)Whilst, in the same vein, Goodman et al notes that;

“Teachers have traditionally been seen as agents of conformity in the language use of their pupils” (Goodman and Goodman cited in Moll 1990)

If the previous sections are brought together, the following points come out.

1 e-mail does not have a fixed set of language rules by which users can agree to conform. This gives e-mail not only the advantage of flexibility but also the disadvantage of the potential for conflict.

2 adults are more affected by this imbalance than children, but children will often look to adults for an understanding of the rules.

3 the choice of language is at the crux of whether a point is made and understood correctly and, as a by product, whether members of a community can form working relationships or not.

Community X students are very often drawn from the pool of so-called at-risk students.

McVay Lynch states that;

“at-risk students [...] are often considered a population that needs special assistance and would not perform well in a web-based environment” (McVay Lynch 2002)

but goes onto to recognise, through Bates (1988) that television as a media is successful with this group of people; thereby inferring that the problem lies not with the Web-based learning - but the application of that facility and perhaps by the language used.

The mentors in Community X are there to reengage the young people through a variety of communication tools of which e-mail is the primary option. This paper suggests that, in order to successfully achieve this reengagement, the mentor will have to overcome the three points made above. Perhaps they would be successful by adopting the colloquial television style language suggested by Bates.

Data Collection and Analysis

The original intention of this research was to correlate the number

of voice mails, multimedia and pictures a Community X mentor used

in their e-mails to their students against the number of formal qualifications

they received. The time taken, however to export these reports into

a file format for harvesting this information was too great to be able

to sample a large enough number of reports in the time given. This was

partly due to software speed across the available network, but also

due to there being 18,000 reports to run on each search for a particular

mentor. It was decided instead only to examine the language used in

the e-mails from mentor to their students, this meant that the reports

only needed to be examined and not to be sorted and exported.

Each week a report is filed on each student by their mentor into a database.

At the time of data collection there were approximately 400 students

on the project, (although not all the students fitted the sample criteria)

so a sample of 25% was collected. Although Cohen, Manion, and Morrison,

(2000) state that a sample of 49% should used on a community of 400,

it is sufficient to discover if a correlation exists and further research

worthwhile. To maintain some level of consistency, students that had

been in only the firstclass community, had only had one

mentor and had been in the community longer than five months were chosen.

A report that their mentor had submitted was chosen and the language

used analysed by means of a five point scale;

-

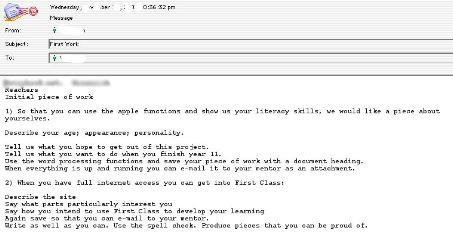

A grading of 1 was given if a mentor used extremely adult language in a teacher role and referred constantly to work, school like assignments given. See fig. 1 in appendix 1.

-

A grading of 2 was given for fairly formal tone of e-mail, still in a teacher role, but less mention of work and accreditation. See fig. 2 in appendix 1.

-

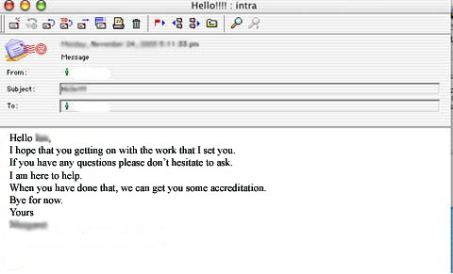

A grading of 3 was given if the e-mails had lost the teacher role, but were still very adult in tone. See fig. 3 in appendix 1.

-

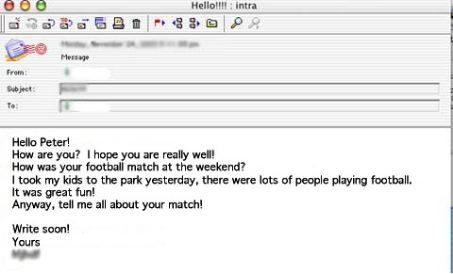

A grading of 4 was given if the language in the e-mail was friendly, but conventional spellings were used. Pictures could also have been included. See fig. 4 in in appendix 1.

-

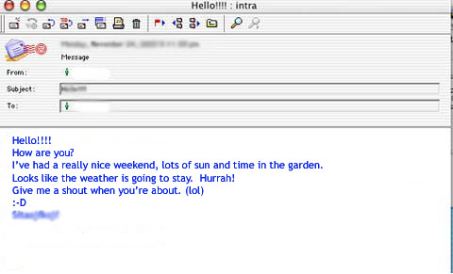

A grading of 5 was given if an e-mail had abbreviations and text spellings. It had to be friendly and chatty with pictures and voice mails. See fig. 5 in appendix 1.

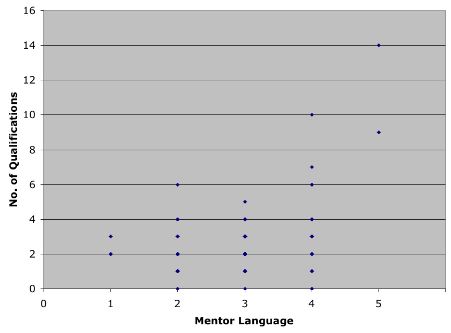

Once a sample of 25% of mentors was collected and the mentor language and tone analysed the number of NCFE part b’s (of NVQ equivalence) recorded. The two figures collected were placed into a spreadsheet and plotted against each other and plotted onto a scatter graph to see if a correlation would appear.

The scatter graph in Fig. 2 clearly shows a correlation between the language that a mentor uses and the number of qualifications a student gets. That is the more friendly a mentor is, the more qualifications their student is likely to gain. Although this is based on a 25% sample, this clearly shows that this line of enquiry is worth pursuing.

fig. 2. Scatter graph showing mentor language plotted against

no. qualifications gained.

In the case of this research two variables were investigated; the language

of the mentor and the number of qualifications their student was awarded.

However in reality there are far more than just these two. A student

may be already extremely engaged and requesting work from a mentor,

so the language used by this mentor may have no bearing on the number

of qualifications. By the same token a student may be totally un-engagable

and so no matter how hard a mentor tries with colloquial tone and voice

messages they may never gain any accreditation. These further variables

suggest that whatever the outcome of this data gathered, more research

should be carried out. An interesting aspect would be to divide up the

mentors and students into male / female categories.

The students that are on the Community X project are divided into

6 different categories; pregnant, sick disaffected, phobic, traveller,

excluded. To truly see if a correlation exits it would be necessary

to divide the data into these different parts.

This research is very much centred on gaining qualifications as

the outcome, however a better outcome would be the analysis of the learning

gains that a student gained. Due to time constraints this was not a

viable option therefore the easily accessible analysis of qualifications

was used rather than the more qualitative interpretation of learning

gains. The weakness of this research is therefore that a student with

phenomenal learning gains that are not shown by qualifications will

have been overlooked. The five criteria qualitative assessment of mentor

language was based on generated specifically for this paper. Given more

time more research would done on linguistics to give a more accurate

and in-depth understanding of mentor language. Due to the short cuts

made in this research there can be less certainty in the results, however,

they are strong enough to indicate not only that these notions are viable,

but that further research should be carried out.

Analysis and Discussion

Analysis of the scatter graph suggests that if a mentor uses a more

friendly and colloquial style of writing the student is more likely to

gain more qualifications. This is supported in Bates (1988 cited in McVay

Lynch 2002) discussion, that television as a media is successful for many

of the ‘at-risk’ students and that the problem with under performing

in Web-based learning is therefore language used by tutors.

As the data was collected it was noted that if an e-mail had a higher

grading (from the 1 to 5 scale) then it was in generally much shorter

in length. Porter also discusses the merits of short e-mails;

“Keep the message short. A short message is much easier to read and respond to than a long, scrollable message” (Porter 1997)

Looking at the e-mails in more depth it could be seen that there were

different ways of making these messages appear short and concise. A

method called chunking was in effect implemented.

“ A chunk or the smallest piece of information that makes sense by itself is a manageable amount of information. [...] Each chunk of information must then be arranged on screen in whatever information will be most useful for the learner” (Porter 1997)

In most cases, where a mentors e-mail had been short and colloquial, it had quite often been accompanied with either an emoticon7 or a cartoon image. Other techniques used were the use of colour, each sentence was placed in a new paragraph and if the colour changed it made it much easier to read. The implications of this are that online tutors need to be aware of not only altering their written language skills to be more informal, but also to be far more inventive in presentation.

However Porter also goes on to say;

“Avoid the cutsies. If you develop a standard signature, header or footer make it look professional. Avoid ‘cutesy’ graphics or quotations. Save the [emoticons] for personal messages to your family or friends.” (Porter 1997)

This disagrees with the research performed here, where it was found that if a mentor used these more personal touches they were more successful. It was discovered that children and adults alike respond much better to both their peers and tutors when a sense of audience was created. This can be done with these “cutesy’ headers and footers. A Community X student responds far better to an e-mail with dollz8 as a signature, it helps them to develop a visualisation of who they are communicating with.

Palloff and Pratt mention the helpful properties of emoticons;

“[Emoticons] helped this group coalesce into a learning community” (Palloff and Pratt 2001)Interestingly they do not include them in their study. This is indicative of the lack of research performed in this area as yet.

Much of the earlier literature discusses the fact that language in e-mails tends to be informal, speech like and a method of keeping in touch with friends and family, (Boone 2001, Mann and Stewart 2000), but very few take the subject of e-mailing past e-mail conventions and use. Salmon (2000) goes into great depth as to when to c.c. e-mails, to be careful with titles, building mailing lists and so on, but does not, as so many other books seem to omit too, discuss appropriate language or how this affects levels of engagement. Most literature does not go into how a tutor should address their student, they do not express an opinion that this friendly style of communication should be used to it’s advantage. Hurley does however state that mentors should have empathy in their e-mails;

“communicating to learners an understanding of how they are feeling[...] respond to the learners language styles, use some of their words in reply.” Hurley (2001)

This has shown to be the case especially in Community X as the children on the project tend to be in need of more attention possibly than those at traditional schooling. A Community X mentor needs to be empathic with their student and use language in their mails very carefully. Many of the students on the project display ‘at-risk’ characteristics and so could well be failed by inappropriate language use.

The analysis of the e-mails has suggested that there could be a definite correlation between language and reengagement. Much research is being conducted currently about online communities and the use of new multimedia technologies, but what the literature has shown is that although e-mail is accepted as a major part of online education, it is not being the subject of any major analysis.

This purpose of this research was to discover whether or not there was a correlation between the language that a mentor used in their e-mails to their students. Secondary research suggested that whilst e-mail is an integral part online learning there is much uncertainty about language rules and implications that this has on successful communication. The primary research in this paper suggested that there is indeed a correlation between the language used between mentor and student. It also challenged conventional teaching by suggesting that a mentor that could project a sense of their personality to their audience by use of emoticons etc. would be more successful in their reengagement levels. This suggests that the training of mentors / facilitators needs to include an understanding of language in the virtual environment as distinct from any other environment that they may have previously experienced. The weakness in the research of this paper could be improved by taking a higher sample rate from the community and then breaking it down the data on the students into their different categories to see if these have any bearing on reengagement levels. It is suggested further research be carried out in the field of language and emoticons used in e-mails and also the levels of engagement in online students with regard to projection of personality to a sense of audience.

REFERENCES

Bartle, R. (2000) History

of the internet

Accessed 22 December 2003

Bates (2002) see McVay Lynch, M. (1988)

Boone, K. (2001) Speech

or writing? Accessed 30 December 2003

British Telecom (2003) bt.com

Accessed 29 December 2003

Brooks, D. (1997) Web-Teaching. A guide to Designing Interactive

Teaching for the World Wide Web New York (USA) Plenum Press

Cohen, L. Manion, L Morrison, K. (2000) Research Methods

in Education London & New York Routledge Falmer

Forsyth, I. (2001) Teaching & Learning Materials & The

Internet London (UK) Kogan Page

Goodman, Y. Goodman, K. see Moll, L.C.

Hurley, J. (2001) Supporting On-Line Learning Winchcombe

(UK) Learning Partners

Licklider, J. see Bartle, R. (1978)

Lockwood, F. Gooley, (2001) A. Innovation in Open & Distance

Learning - Successful Development of Online and Web-Based Learning

London (UK) Kogan Page

Mann, C.Stewart, F. (2000) Internet Communication and Qualitative

Research: A Handbook for Researching Online

London (UK) Sage Publications

Mason, R. (1994) Using Communications Media in Open and Flexible

Learning London (UK) Kogan Page

McVay Lynch, M. (2002) The Online Educator - A guide

to Creating the Virtual Classroom London (UK) Routledge Falmer

Moll, L.C. (1990) Vygotsky and Education. Instructional Implications

and applications of Sociohistorical psychology Cambridge (UK)

Cambridge University Press

Murphy, D. Walker, R. Webb, G. (2001) Online Learning

and Teaching with Technology London (UK) Kogan Page

Palloff, R. Pratt, K.(2001) Lessons from the Cyberspace Classroom

San Francisco (USA) Jossey-Bass

Porter, L. (1997) Creating the Virtual Classroom, distance learning

with the internet. New York (USA) Wiley Computer Publishing

Simpson, O. (1999) Supporting Students in Online, Open and Distance

Learning London (UK) Kogan Page

Vygotsky (1978) see Moll L.C.

FURTHER READING

Alexander S. Boud, D. (2001) Learners still learn from experience

when online in teaching & learning online London (UK) Kogan

Page

Bates A.W.T. (1995) Technology, Open Learning and Distance Education

New York (USA) Routledge

Clarke, A. (2001) Designing Computer-Based Learning Materials

Hampshire (UK) Gower

Clarke, A. (2002) Online Learning and Social Exclusion

Leicester (UK) NIACE

Duckworth, J. (2002) Community X external evaluation

Chelmsford (UK) Ultralab

Duggleby, J. (2000) How to be an Online Tutor Hampshire

(UK) Gower

French, D. Hale, C. et al (1999) Internet Based Learning

London (UK) Kogan Page

Frith, D. Macintosh H.G A (1984) Teachers Guide to Assessment

Cheltenham (UK) Stanley Thornes

Jain, K.(2003) Motivating

Factors in E-learning A Case Study of UNITAR Accessed 28 December

2003

Joliffe, A. Ritter J. Stevens, D. (2001)The

Online Learning Handbook London (UK) Kogan Page

Kearsley, G. (2000) Online Education - Learning and Teaching

in Cyberspace London (UK) Wadsworth Publishing Company

Murray, L. Lawrence, B.(2000) Practitioner-Based Enquiry, Principles

for Postgraduate Research London (UK) Falmer Press

Rudduck, J. McIntyre D. (1998) Challenges for Educational

Research London (UK) Paul Chapman Publishing

Salmon, G. (2000) E-Moderating London (UK) Kogan Page

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice. Learning, Meaning

and Identity Cambridge (UK) Cambridge University Press

Wenger, E. et al (2002) Cultivating Communities of Practice

Boston (USA) HBSP Press

Werry, C. Mowbray, M. (2001) Online Communities USA

Prentice Hall PTR

Wolfe, C. (2000) Learning and Teaching on the World Wide Web

London (UK) Academic Press

WEB LINKS

Atherton, J.S. (2003) Learning

and Teaching UK Accessed 21 December 2003

Bradshaw, P. (2002) Shared

Learning and Issues arising Accessed 22 December 2003

www.kolar.org

Accessed 22 December 2003

McGuire, L. (2001) Top

10 criteria for a well-designed online course Accessed 22 December

2003

Myers Briggs Working

out your Myers Briggs type Accessed 21 December 2003

Ramondt, L. & Chapman C.(1998) Online

Learning Communities Accessed: 21 December 2003

Rovai, P. (2002) International

Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning Accessed: 21 December

2003

Sloan Consortium (The) aln.org/

Accessed 21 December 2003

Wenger, E. Homepage

of E. Wenger Accessed 21 December 2003

Wilson, C. Learning Styles: Nurturing the genius

in each child Accessed: 21 December 2003

Winters, E. Benjamin

Blooms Taxonomy Accessed: 21 December 2003

Full Circle Associates fullcirc.com

Accessed: 21 December 2003

Examples of Mentor language gradings